Throughout the 27th Annual Whitaker St. Louis International Film Festival (SLIFF), the writers at the Lens will be spotlighting their favorite narrative and documentary films on this year's festival schedule. Each day, our critics will discuss can't-miss festival highlights, foreign gems that have already made an international splash, and smaller cinematic teasures that might have overwise been overlooked – just in time for you to snap up tickets.

Far too often, biographical documentaries end up as mere delivery devices for drowsy, unedifying banality. Perhaps it’s simply that the nine out of ten biodocs all seem to follow the same playbook, spinning a neat and tidy narrative from a chronological overview of the subject’s life, usually by relying on archival footage and talking-head reminisces. The more memorable biographical films are often those that break this well-worn mold. Just this year, Sophie Fiennes’ Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami interrogated its subject almost entirely through present-day concert footage and intimate, vérité video. Meanwhile, Kevin Macdonald’s Whitney adopted a vivid exposé approach, reminding the viewer of forgotten facts and digging (sometimes uncomfortably) into the Queen of Pop’s hazy complexities. And Eugene Jarecki’s The King turned the biodoc inside out and took it on the road, using Elvis Presley’s life to cross-examine the American experience itself.

Director Tiffany Bartok’s Larger Than Life: The Kevyn Aucoin Story isn’t daring or questioning in the manner of those films, but it discovers a comparable forcefulness simply by doing the biodoc fundamentals exceptionally well. She doesn’t reinvent the wheel so much as reaffirm the reliable robustness of its familiar shape. In recounting the striking accomplishments of the late American makeup artist Kevyn Aucoin, Larger relies on all the usual hallmarks of the subgenre: the unlikely Horatio Alger tale, distilled and neatly arranged; the plethora of vintage photos, press clippings, and home videos; the parade of family, friends, and colleagues who wistfully share their cherished anecdotes. However, Bartok shapes these standard raw materials into a vivacious, authentically touching portrait of a man who, in his mere 40 years on Earth, changed the landscape of beauty, fashion, and celebrity in sneakily profound ways.

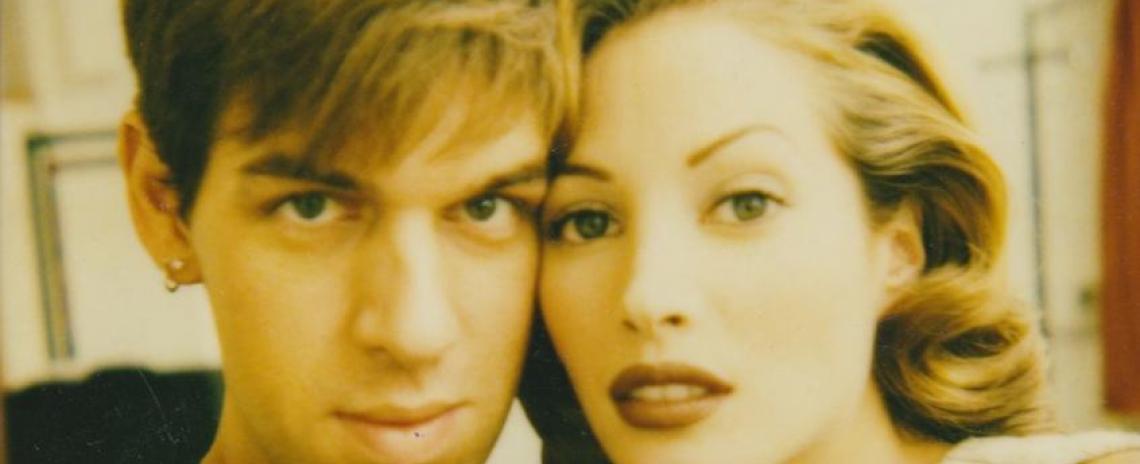

In 2018, YouTube is a repository of countless how-to makeup videos, a resource that enables eager viewers (women, men, and anyone else) to soak up thousands of hours of accumulated professional and DIY wisdom on the art of beauty. Arguably, this dazzling, streamable compendium of knowledge would not exist at its present scale without the influence of Kevyn Aucoin, a gangly boy from Lafayette, La. who adored cosmetics and photography. Perhaps as repayment for the tribulations he suffered growing up gay in the small-town South, the universe smiled on Aucoin when he moved to New York, as he landed himself a gig making up models at Vogue just eight months after his arrival. Over the ensuing years, Acouin established himself as a coveted corner-man for models, actors, and other celebrities. His technique was peerless, his passion infectious, and his giant yet nimble hands a curious source of comfort in the frenetic backstage world. At the height of his renown, he had the sort of professional caché that was unheard of for makeup artists – Cindy Crawford could bring a European photo shoot to a halt to have Aucoin flown to her side.

A fluffier sort of biodoc might have leaned overwhelmingly into the film’s cavalcade of glowing testimonials from seemingly dozens of famous faces – which are, admittedly, a pleasure. (A marvelous detail: Regardless of fame, all the talking heads are identified onscreen as “Actor”, “Model”, “Designer”, and the like, with one exception. Cher is simply "Cher", because she needs no further introduction.) It’s obvious that not only Aucoin’s talents but also his warm, lively personality left a deep impression on the people with whom he worked. However, Bartok also pushes deeper into the man’s cultural legacy, showing how his innovations shaped the way that millions of people view and approach their own beauty. It was Aucoin who developed and popularized the highly sculpted contouring that came to dominate the makeup world in the early 21st century, and it was Aucoin who pioneered more natural cosmetic shades that could accommodate the broad swath of human skin tones. More intangibly but just as essentially, he proffered an actual ethos in his three best-selilng makeup books, one that valued radical self-love and sought to tease each person’s inherent beauty to the surface.

Aurcoin was an almost obsessive self-documenter, and as such Bartok is blessed with an enviable wealth of letters, mementos, photos, and home movies to draw on. These reveal her subject’s unselfconscious private joys, but also his dogged insecurities, not to mention the unthinkable pain he endured as his tumor-associated acromegaly – the same characteristic that made him tower over a room and bestowed him with those colossal hands – took its toll on his body. Bartok strikes a careful balance in addressing Aucoin’s addiction to painkillers and his eventual death in 2002 due to an overdose of the same. Larger Than Life is not needlessly coy about this ugly, heartbreaking aspect of his life, nor does the film gloss over it as though it were inessential to an understanding of the man. However, Bartok emphasizes – modestly but firmly – that Aucoin is worthy of wider recognition primarily due to his resounding professional achievements, rather than because he represents some tragic case study in disability or addiction. Even viewers who know nothing about cosmetics, fashion, and beauty will find Larger edifying and inspiring, an illustration that raw, revolutionary talent paired with an earnest, generous soul can make the world a little less ugly.

Larger Than Life: The Kevyn Aucoin Story screens Monday, Nov. 5 at 7:30 p.m. at .ZACK.