There is nothing all that groundbreaking about Hammer, a muggy, frantic crime drama that is the sophomore feature from Canadian writer-director Christian Sparkes (Cast No Shadow). The film faithfully adheres to the indie-crime-thriller playbook: The story snakes through the grubby underbelly of a small town, following a desperate, unremarkable mope as he claws his way out of a perilous situation that is largely of his own making. The film’s excellent lead performances and artful execution distinguish it from comparable generic offerings, but what leaves the most striking impression is the emotional entry point that Sparkes finds into the story. Hammer is less about the damned soul of the luckless criminal in question, Chris (Mark O’Brien), than about the young man’s thorny, stunted relationship with his father, Stephen (Will Patton), a recently retired schoolteacher. Over the course of one violent, unforgiving, and at times unbelievable day, the soft-spoken, straight-laced Stephen is dragged – not entirely unwillingly – into the bloody chaos of Chris’ life.

Sparkes establishes the film’s scenario with great economy, trusting in the familiarity of the genre components and the severe yet sticky emotional stakes. A small-time, small-town reprobate from Ontario, the twentysomething Chris is returning from a drug-smuggling run across the U.S. border with two duffel bags loaded with cash. At some unspecified point in the past, Chris’ parents, Stephen and Karen (Vikie Papavs), threw him out of their house on account of his drug use and criminal mischief, and they seem to have no clue that his illicit activities have since escalated. Indeed, Stephen nurtures a stubborn belief that their act of tough love will eventually motivate Chris to clean up his act. He curtly shuts down Karen’s proposal to move her dementia-afflicted father into Chris’ room, on the grounds that their prodigal son will return any day now. Chris’ younger brother, Jeremy (Connor Price), has his doubts, however. As he observes to his mother, “You treat someone like an outsider long enough, eventually they become an outsider.”

Chris meets up with petty drug kingpin Adams (Ben Cotton) and Adams’ girlfriend, Lori (Dayle McLeod), on a deserted forest back road to hand over the smuggled cash. However, the group is ambushed by a helmeted figure on a motorcycle who stages an accident to block their path. Adams manages to subdue the attacker but then turns in a paranoid frenzy on Chris, whom he suspects has betrayed him. (He has, as it turns out.) Chris escapes the scene on the motorcycle with the money and a gravely wounded Lori, eventually concealing both the bags and the bleeding woman in a cornfield. It is at this point that Chris’ criminal life collides with his fraught but more prosaic family melodrama. While out on an errand, Stephen spies his bloodied son roaring through town on the motorcycle. This distressing sight prompts the older man to stop and confront Chris, who spins a panicky, self-serving story about his dilemma, leaving out certain damning details.

So begins a Long Day of the Soul for father and son, as Stephen does his level best to extricate Chris from a death sentence at the hands of a vengeful crime boss. Unfortunately, Chris can’t remember where he stashed the money from the drug deal – every acre of cornfield looking much like the last – so his immediate goal is to pull together a quick stack of cash to purchase protection from some local muscle-for-hire. Stephen, however, is more alarmed at how unthinkingly Chris abandoned a mortally wounded woman to bleed out in the middle of nowhere, and how little thought he gives to finding her and getting her medical attention. Moreover, every time he catches Chris in an obvious lie, Stephen’s own relatively myopic view of his son erodes a little more, and his decision to evict Chris into the world to fend for himself seems like a bigger blunder. Was his son always a craven, reckless little sociopath? Or did pushing him away hasten his downward slide? At times, Stephen’s willingness to follow along with Chris as they careen from one mini-crisis to the next seems to be less about paternal protectiveness than a need to pinpoint exactly where his parenting went awry.

Given that its plot is studded with questionable coincidences and oddball detours– there is a particularly tense and memorable set piece involving a crooked pawnshop owner – Hammer could easily have been staged as Coens-flavored dark comedy about criminal ineptitude. Instead, Sparkes presents things completely straight, favoring a gritty, tragic tone that emphasizes the tangibility of the characters’ plight and the searing guilt that presses down relentlessly on both father and son like a hot, sizzling stone. Although the film is set in Ontario, the sweltering late-summer backdrop and the emphasis on generational cycles of pathology give the film a definite Southern Gothic shading. There is a strong streak of noir nihilism to the whole thing as well, underlining the inherent ugliness and pointlessness of humanity’s struggles.

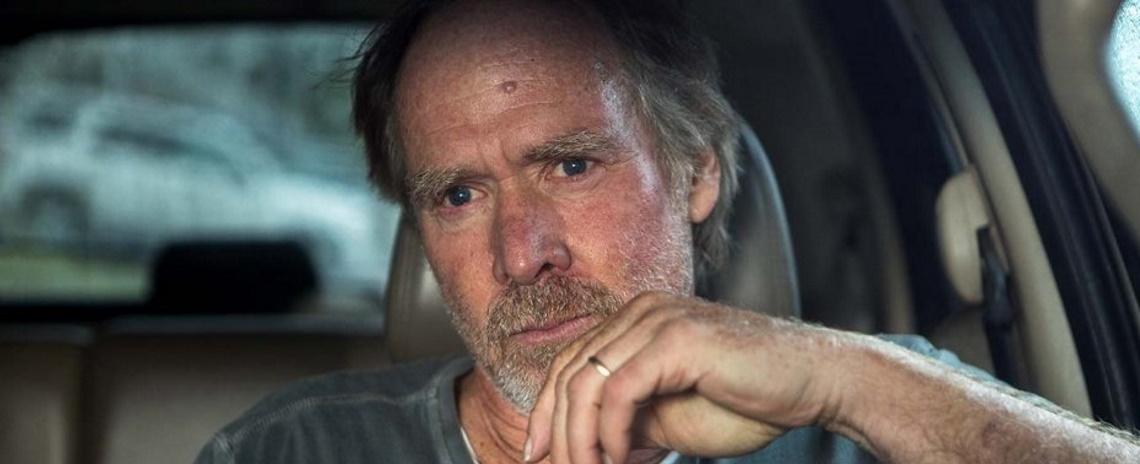

Hammer is conspicuous as a rare starring vehicle for Patton, a prolific character actor who is equally comfortable in genre studio fare like Halloween (2018) and in indie features like American Honey (2016). American cinephiles probably know Patton best from two of director Kelly Reichardt’s masterworks, Wendy and Lucy (2008) and Meek’s Cutoff (2011), the latter of which is a particularly fine showcase for Patton’s abilities. The actor possesses one of those rare faces that can realistically convey the act of thinking, his countenance shifting and rumbling as his character wordlessly processes information or makes a critical decision. Hammer gives Patton plenty of these moments, as Stephen is repeatedly thrust into the cascading dilemmas and disasters that result from his son’s criminal incompetence. It certainly doesn’t hurt that Patton can also exude a beefy, intimidating physical presence when needed, given the cavalcade of lowlifes that Stephen and Chris end up confronting. O’Brien is in excellent form as well: It is no mean feat to make sweaty desperation look so convincing for such a sustained duration. Although Chris is exactly the impulsive, cowardly loser he appears to be at first glance, O’Brien gradually allows the character’s buried, less obvious resentments to surface, giving him some needed depth. However, although O’Brien ends up with slightly more screen time, Hammer is unquestionably Patton’s show.

Sparkes’ visual approach strikes a fine balance between stripped-down, handheld realism and more impressionistic visuals. The director favors jittery, claustrophobic close and medium shots for dialogue scenes, which are assembled by editor Jorge Weisz in a hectic manner that seems designed to maximize the viewer’s anxiety. In between these suffocating sequences, however, the filmmaker frequently pulls back, gazing almost languidly at the town’s sad, sagging storefronts or the lonesome beauty of the surrounding farmlands – as though giving viewers a respite to catch their breath. Occasionally, Sparkes and cinematographer Mike McLaughlin push in close on a striking image, whether to emphasize its metaphorical significance (a grass snake improbably devouring its own tail) or to simply linger on its abstract loveliness (iron-gray raindrops streaking a car window). Indeed, McLaughlin makes vivid use of the widescreen format throughout – a rarity, given how often lo-fi indies end up wasting the extra visual real estate of the 2.35:1 aspect ratio.

It is these sorts of touches that lend Hammer a dose of cinematic vitality, lifting it above the workaday mechanics of its crime-thriller plot. Yet Sparkes’ directorial hand remains relatively restrained overall, privileging character and story over any ambition to craft the art-film version of a vicious small-town noir. Hammer never exhibits much interest in breaking free from generic formulae, and it is largely content to rely on straightforward pell-mell escalation rather than more substantive dramatic shifts and upheavals. There are not any “twists” per se, just a bad situation that gets worse and worse, sometimes in unforeseen ways. Still, it is always a pleasant surprise when a small, taut thriller such as Hammer reaffirms that robust cinema can be produced on a modest budget. Moreover, a story that could have been fodder for grimy exploitation or cynical absurdity becomes in Sparkes’ hands a sobering narrative with compelling performances and authentic thematic weight.

Grade: B-

Hammer is now available to rent from major online platforms.