Pedro Almodóvar began his filmmaking career by grabbing his audiences by their lapels and shouting in their faces. His 1980 debut, Pepi, Luci, y Bom, is a queer post-punk screwball comedy on a coke bender. Twenty-three years later, however, he was picking up an Academy Award for his Talk to Her screenplay. The rebel hadn’t lost his anti-establishment values. To the contrary, his 2002 coma-rape romance was just as provocative as his early work, but he was now queasily jerking tears instead of jerking off.

Parallel Mothers finds the iconoclast-turned-arthouse stalwart putting a hand on his audience’s shoulders, leaning into their ears and whispering to them. Nevertheless, his messages are still bold, vibrating with the same boundless emotion as his earlier, more outwardly expressive work. His latest is among his most refined, and not in a tony, more palatable sense this word might suggest. Its over-the-top complications of possible baby swaps, infidelity, tragic death, fluid sexuality, secrets, and lies are still titillating, but once its dual narratives are fully intertwined, Parallel Mothers presents one of the director’s most clear-eyed self-examinations.

That’s important to the work of an autobiographical artist like Almodóvar. His previous feature, 2019’s Pain & Glory, plumbed the depths of his own experience as an aging popular artist through a fictional stand-in (performed by longtime stock company player Antonio Banderas, in a deservedly lauded turn). Parallel Mothers goes even deeper. After years of backgrounding Spain’s dictatorial decades, this the first time the director forefronts the violent political history of his home country.

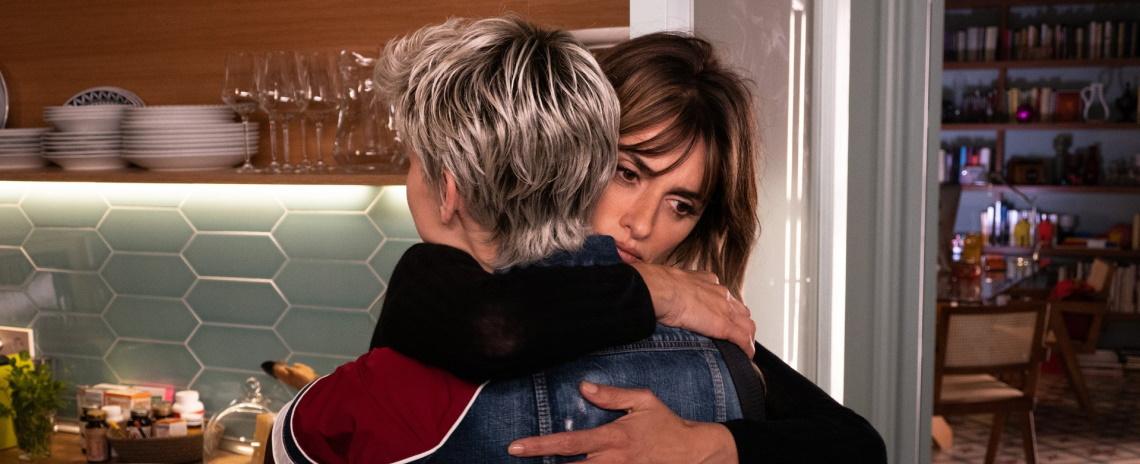

Here, he presents a tricky proposition and asks viewers to once again suspend disbelief in processing the grand convolutions that are typical of his stories. They must also suspend understanding his purpose until the film’s final moment. Two seemingly disparate strands will eventually cohere in a statement as bold as his written paean to womankind and motherhood at the end of his 1999 masterpiece, All About My Mother. In the first strand, Janis (Penélope Cruz, so strong here she deserves co-authorship) is an affluent fashion photographer who enlists archaeologist Arturo (Israel ElejaldeI) with exhuming her family’s remains. Their brutal 1944 murder and burial in a trench in their rural community by the national military have been memorialized in stories passed down from generation to generation. Janis believes that she and her family can only complete their inherited mourning once their dead have been properly buried.

In the second strand, Arturo and Janis complicate things further by beginning an affair. As this is Almodóvar, smash-cut to nine months later, and Janis is heavily panting in a hospital room on the verge of having the married man’s baby. She shares the room with teenager Ana (a remarkable Milena Smit), who’s also about to be a single first-time mother. They form a tight bond and eventually have concurrent difficult births that land their newborns in the NICU.

Their paths will later cross once again, but only after Arturo plants the idea in Janis’ head that their baby may not actually be their baby. Janis’ path, however, will include many detours as she buries truths and perpetuates trauma, justifying her actions as maternal and righteous. The film’s pleading, call-to-action final shot parallels this personal journey with the political one and colors a pat cliché in illuminating shades. Maybe the truth will set them free: Spain, the haunted villagers, and Janis and her non-traditional family unit.

Parallel Mothers is the second Almodóvar since 2015’s Julieta, which seemed to signal a third — maybe fourth or fifth, depending on how thinly you want to slice his oeuvre — phase in the director’s career. (It also marked the long-awaited return of Almodóvar fan favorite Rossy De Palma, who plays a motherly best friend to Janis here.) Adapted from stories by popular Canadian author Alice Munro, Almodóvar was labeled by many as a more mature artist yet again, but with hints of disappointment. His oft-expressive camera and trademark bold color palette were subdued, but these are qualities Mothers shares to its benefit (although its digital photography is occasionally phony and garish). Close-ups and conversations drive the slowed rhythms. While characters untangle the knotty plot, the camera focuses on and frames them in ways that betray yet another parallel story of their internal conflicts.

However, this is still the Almodóvar who wears his influences on his designer sleeves. He uses the melodrama hallmarks of Douglas Sirk, with stifling, color-splashed Madrid interiors explicating degrees of privilege. Alfred Hitchcock’s shadow looms large over the director and his Mothers, too, as they wade through a Catholic ethos with a twitch of the death nerve and the latest Bernard Herrmann-esqe score by Alberto Iglesias.

There are countless others influences — the work of some of them line Janis’ carefully arranged bookshelves in her carefully arranged home. However, playwrights Tennessee Williams and Federico García Lorca surely complete the director’s Mount Rushmore. Their tragic and poetic hothouses are built with outsiders’ political and social ideologies that are similar to Almodóvar’s, a gay man who grew up in a once-fascist state. Lorca is explicitly called out when Teresa (Aitana Sánchez-Gijón), Ana’s mother (yes, yet another mother), performs a scene from his Dona Rosita the Spinster, about the pain of being a mother and an autonomous person at the same time.

The resulting synthesis of all these sensibilities is uniquely Pedro. It’s so recognizable that, over four decades of filmmaking, his name has become synonymous with U.S. moviegoers’ notions of “world cinema” (and in turn he’s become one of the few easy bets at this specialty box office). As reductive as this might seem, the great Parallel Mothers isn’t likely to change that.

Rating: B+

Parallel Mothers is now playing in select theaters.