Plenty of films – both narrative and documentary – have depicted life inside the American prison industrial complex, but few works have looked at the flip side: the family left behind, who must somehow muddle forward with their lives. Director Garret Bradley’s sensitive and ingenious new film Time does just that. It tells the story of Sibil Richardson (aka Fox Rich) and her children, who wait (and work) diligently for husband Robert’s parole from an unduly harsh 60-year prison sentence. A different kind of documentary might have used a strictly chronological approach to emphasize the mercilessly slow creep of time’s arrow, the seemingly endless parade of X’s across the calendar. Bradley – tackling her first documentary feature after a decade of narratives (Below Dreams, Cover Me), shorts, and television work – is up to something different. Flickering back and forth through the years in almost lyrical fashion, she makes Time a much richer experience: partly an impassioned advocacy doc and partly a heartsick, impressionistic portrait of an under-represented side of American life.

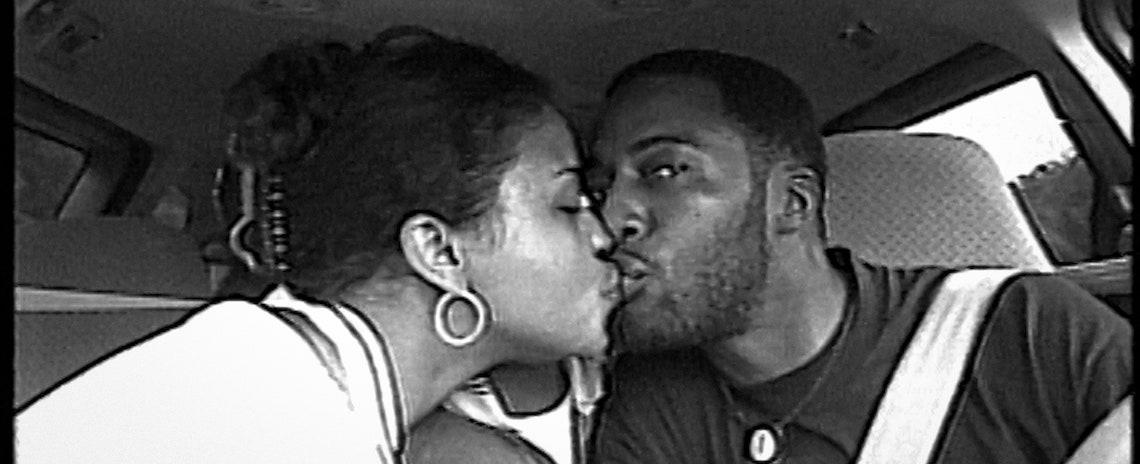

The filmmaker has marshaled her feature from a combination of gorgeous original black-and-white footage and Fox Rich’s wealth of MiniDV home videos – the latter captured to document the family’s growth, setbacks, and triumphs for the benefit for her incarcerated husband. Although there is a broadly chronological arc to the film’s narrative, Bradley scrambles the material just enough to create the sensation of a blurry limbo. Time seems to slip backward and forward, emphasizing that for as long as Robert is behind bars, his family remains in a kind of revolving stasis. They and the world around them might change, but the fundamental reality of their situation never seems to change. Fox is at first a struggling young mother, then a middle-age matriarch and entrepreneur, and then she is young again. Her children are rambunctious toddlers, then strapping college graduates, then toddlers again. Life goes on, except it doesn’t. It is then and it is now, and Robert is still in prison.

Significantly, Time is not a documentary about a wrongful conviction. The facts are not in dispute: In 1997, the Richardsons attempted to rob a Shreveport, La., credit union at gunpoint. Fox describes their mindset as one of desperation: The retail hip-hop clothing business she and her husband had worked hard to build was on the verge of financial collapse. She is vague when discussing the details of the crime itself, perhaps understandably, although this evasiveness slightly undercuts the film’s story of contrition and rehabilitation. Regardless, Fox pled guilty in exchange for a 12-year sentence, and she was paroled after less than four years. Robert opted for trial and was handed a gutting punishment: six decades in Louisiana’s notorious Angola penitentiary, with no possibility for parole. Even for a twentysomething, this was, in effect, a guarantee that he would perish behind bars.

After serving her own time, Fox picks up the fragments of her life and re-forges them into a startling success story: raising six high-spirited boys, all them remarkable in their own right; building a thriving auto-dealership business; and transforming herself into an ardent activist for criminal-justice reform. It’s plain that Robert’s disproportionate 60-year sentence is not, strictly speaking, for pointing a gun at a credit-union teller: It’s for doing so while being Black. Blessed with the sort of charisma, aplomb, and fastidious way with words that would make most politicians envious, Fox describes herself as an “abolitionist,” working tirelessly to create awareness of (and rectify) the inequitable penalties that Black men endure in the U.S. justice system. She also labors perpetually on Robert’s legal appeal, arguing that his onerous original sentence and subsequent model-prisoner behavior warrant the overturn of his parole prohibition. Year after year, she and the family’s attorneys articulate this argument in scrupulous but heartfelt terms, to no avail. Most of the time, Fox’s patience and positivity are seemingly boundless – “Next year will be the year,” she assures herself after yet another defeat – but the accumulated burden of the innumerable disappointments clearly weighs on her spirit.

The picture that emerges from Bradley’s feature is that of an oppressive holding pattern, a fog of despair and déjà vu that colors even the Richardson family’s happiest moments. Like the titular protagonists in Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad and Audrey’s Niffenegger’s The Time Traveler’s Wife, Fox is defined (in part) by the act of waiting. She’s also fighting, of course, but her unflappable resolve and righteous anger often seem to be swallowed by the sheer crushing inertness of her ordeal. Time’s most indelible scene is one that repeats over and over: Fox phones a court clerk and inquires with crisp, apologetic politeness whether they have any news regarding Robert’s appeal. Bradley presents these sequences – which play like a Kafka-esque nightmare by way of latter-day Frederick Wiseman – in a manner that maximizes their disheartening absurdity. No matter how hard Fox works to secure Robert’s parole, she is ultimately beholden to forces beyond her control, whether four centuries of systemic racism or one tetchy civil servant more concerned with their lunch break than an inmate’s legal proceedings.

It’s easy to see why Fox’s remarkable tale ensnared Bradley’s creative imagination and journalistic passion. Fox herself is an instantly alluring, formidable figure, keenly aware of how to use her looks, voice, and story to convey the injustice of her husband’s plight and the struggles that her family has weathered. The fact that Robert was, in fact, guilty of his crime (as was Fox) is both Time’s most vexing weakness and its sneakiest strength. Although this means that the Richardsons lack the picture-perfect moral authority of, say, a Sister Helen Prejean, it also sharpens Time’s legal and ethical arguments. Convicted individuals shouldn’t need to be innocent to be protected from the cruel and unusual punishment of excessive prison sentences. (One thinks of that ghastly phrase so often invoked when incidents of anti-Black police brutality come to light: “They were no angels.”) What purpose is served – beyond the purely punitive – in locking away a person for the rest of their life, all for one terrible, stupid mistake? What purpose is served in banishing their spouse and children to a legal and domestic phantom zone, where time marches on while standing still? Bradley’s film is, above all else, a radical call for empathy, an appeal to imagine how long our own fidelity and fortitude would persist in Fox Rich’s circumstances. Would we possess the strength she exhibits? Should anyone have to?

Rating: B+

Time is now available to stream from Amazon Prime.