The 13th Annual Robert Classic French Film Festival celebrates St. Louis’ Gallic heritage and France’s cinematic legacy. As a preface to the August 28 festival screening of Jacques Deray's La Piscine (1969), Kayla McCulloch – staff film critic for CSL’s blog The Lens – has provided the following appreciation of the film.

La Piscine: Trouble in Paradise

By Kayla McCulloch

1969 / France, Italy / 122 min. / Dir. by Jacques Deray / Opened in U.S. theaters in August 1970

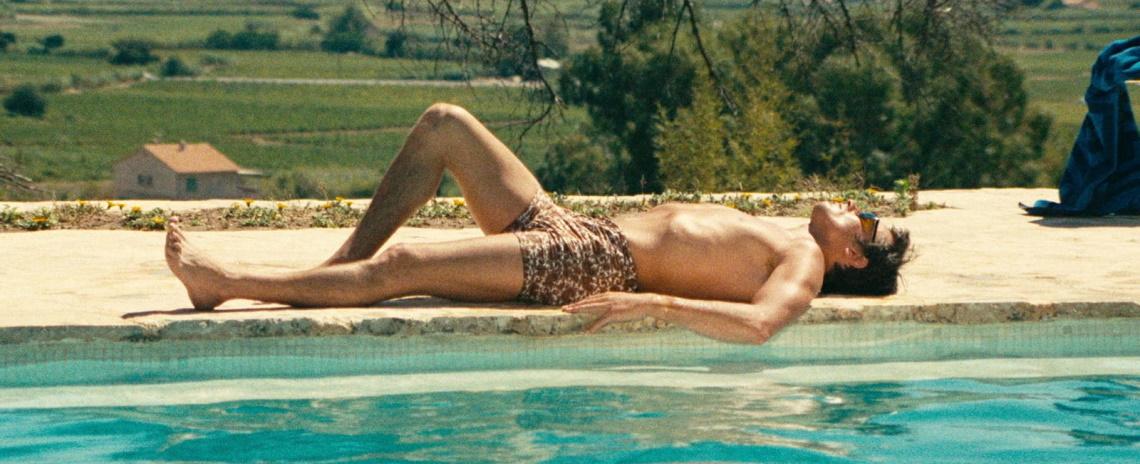

Jean-Paul (Alain Delon) lays poolside, trunks still damp from a recent dip in the shimmering blue water overlooking the French countryside, his sunglasses blocking out the rays that beat down on his already bronze skin. One hand dangles in the meticulously maintained pool, while the other brings an almost-finished drink up from his side and waterfalls the last of it into his mouth. He leaves the condensation-coated glass there on his face, resting on his nose and his lips. Jean-Paul’s life will never be as tranquil as it is here at the start of Jacques Deray’s La Piscine (1969). Soon Marianne (Romy Schneider) will dive in and splash him, she’ll slip out of the pool and onto his chest, they’ll fool around a bit on the sweltering concrete, and — right when they’re at their most amorous — a phone call from inside the villa will change the trajectory of their lives forever.

Jean-Paul torments Marianne for answering the call, and she torments him back with some unexpected news. Their mutual friend Harry (Maurice Ronet) — more Marianne’s friend, really — just so happens to be vacationing nearby, and he’s going to be stopping by with his daughter Pénélope (Jane Birkin). Already, with just a handful of scenes, Jacques Deray has effectively evoked a few visceral feelings: the serenity of a perfect vacation, the frustration of a beautiful moment interrupted, and the resentment one feels when the attention they thought was theirs is suddenly someone else’s. These budding feelings are foundational to La Piscine — and vacations in general — and they only proliferate from here.

The sight of Marianne’s arms wrapped around Harry’s neck makes Jean-Paul seethe. Those arms were wrapped around his neck earlier that same day, and they were still supposed to be there still — not cradling this obnoxious man. Regardless, Jean-Paul, being the bigger man, puts on a friendly face and welcomes Harry and Pénélope to their French Riviera oasis as if they were meant to arrive all along. Picking up on this convincing faux-genial energy, Marianne asks Henry and Pénélope to stay with them at the villa rather than in Saint-Tropez. Of course, to Jean-Paul’s chagrin, Henry accepts. The next several days consist of biting passive aggression, galling mind games, and burgeoning romance that culminates in a shocking instance of brutality — and it all goes back to that unforeseen phone call that would have been better left unanswered.

The idea of trouble in paradise is endlessly appealing to both filmmakers and audiences alike, and for a good reason: Everyone wants to go on the perfect getaway, but once it’s actually embarked upon, everyone eventually realizes that there’s really no such thing as a true escape. Whether it’s the disappointment of a locale that isn’t as picturesque as it seemed in the brochure, the nagging responsibilities left behind in the outside world that can never truly be ignored, or the long list of things to do and places to see that never comes close to being completed, a dramatized vacation from hell is universally relatable because practically everyone’s been there before. Just look at the multiple re-imaginings of Deray’s film (François Ozon’s Swimming Pool [2003] and Luca Guadagnino’s A Bigger Splash [2015]), the current success of Mike White’s HBO series The White Lotus (2021- ), or the lingering cultural relevancy of National Lampoon’s long-running Vacation film series (or at least the first two entries).

As a matter of fact, The White Lotus often feels like a direct descendant of La Piscine: the show opens with a scene that recalls the final act of Deray’s film, then hops back in time one week to walk viewers through the series of uncomfortably tense encounters that led one yet-to-be-revealed individual from the cast of cringe-worthy characters to commit a heinous act of violence against another. Instead of traditional dramatic devices like fistfights or screaming matches, The White Lotus draws from La Piscine’s reliance on microaggressions and apathetic behavior for its central conflict. Despite the 52 years and nearly 8,000 miles that separate White’s Hawaii-set series and Deray’s French feature, their shared universality is evident — an unwillingness to come to terms with the fact that Murphy’s law doesn’t make exceptions for vacation plans.

While not all trips end in felonies (thankfully), the universe never passes up on a chance to remind a bourgeois brat that a vacation is a privilege and not a right. It’s a unifying motif across all these aforementioned titles and many other works that fall under the thematic umbrella. Any sense of entitlement or ungratefulness from a vacationer will be swiftly met with a cosmic reminder that some people would kill for the opportunity to have a respite from the obligations of the real world. (And, as seen in La Piscine, some people literally do kill for that opportunity.) Sure, Harry and Pénélope’s arrival wasn’t what Jean-Paul had planned for his and Marielle’s Côte d'Azur holiday, but is it really that bad? After all, doesn’t it sound better to be miserable in paradise than miserable at home? Perhaps this is easier said than felt, but nevertheless, those terrible vacation memories help to make the delightful ones more fulfilling. The terrible, cramped car ride ends in a gorgeous sunset over the ocean. The crying baby and the rocky turbulence on the flight lead to the stoic stillness of the mountains. These contrary forces ultimately bring balance to the trip, and accepting the good with the bad brings a true, profound peace that, by the end of La Piscine, Jean-Paul could only dream of.