Talk of “disruption” in the movie marketplace took on a terrifying new meaning in 2020, as theaters closed indefinitely, limited show times, or otherwise adjusted to the new reality where studios were no longer pumping out new wide-release features at a steady clip. Even as the world convulsed from the ravages of the Covid-19 pandemic, however, the content somehow just kept coming. There was certainly no shortage of films in 2020: Hollywood blockbusters scheduled for release last year were hastily shifted to streaming platforms or simply kicked down the road to 2021 and beyond, but a legion of smaller films stepped up to fill the void. (Or, at least, the gaps in restless cinephiles’ viewing logs.)

Yes, 2020 was the year that streaming, video on demand, physical media, backyard screenings, drive-in theaters, and other substitutes for traditional first-run distribution became the default means by which Americans experienced the movies. Although there’s no true substitute for the communal, theatrical viewing experience – to say nothing of film festivals – determined cinephiles and casual movie lovers alike were able to use such means to stay abreast of the year’s still-impressive offerings.

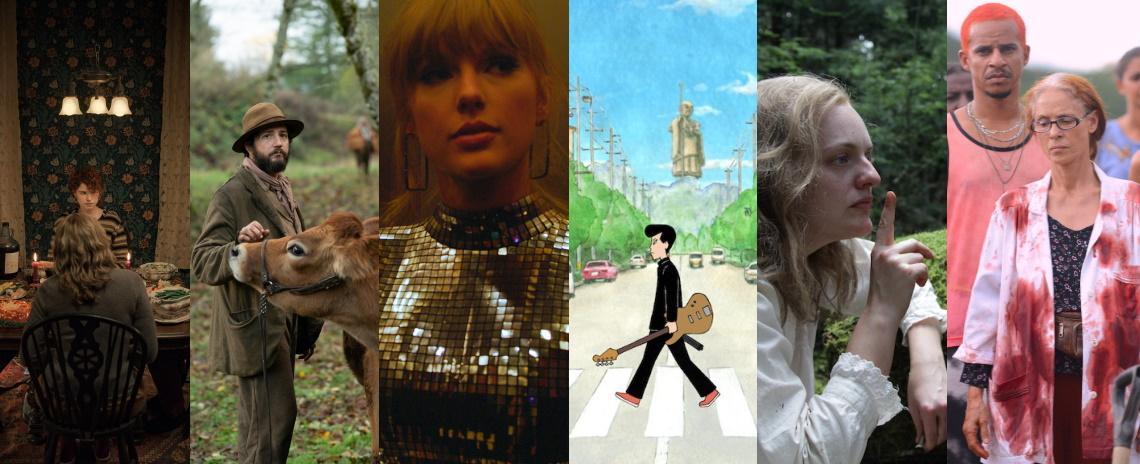

If there was a slender silver lining to 2020’s abundant miseries, it was the apparent ascendency of films directed, written, and/or headlined by women – both in the general release schedule and in late-year awards and best-of discussions. Longtime indie darlings such as Josephine Decker, Julia Hart, Eliza Hittman, Kirsten Johnson, Kitty Green, Kelly Reichardt, Lana Wilson, and Chloé Zhao delivered some of their best and highest-profile work to date. Debut features from Radha Blank, Maïmouna Doucouré, Emerald Fennnell, Natalie Erika James, Regina King, and Channing Godfrey Peoples captured critical notices. Women directors dominated the romcom cultural conversation (Autumn de Wilde, Clea DuVall, Natalie Krinsky, Alice Wu), but they also took the action-cinema helm (Niko Caro, Gina Prince-Bythewood, Patty Jenkins, Cathy Yan) – even as Christopher Nolan was stubbornly clinging to it. Whether these developments represent the beginning of a long-overdue realignment of film-production culture or merely a statistical blip in an aberrant release year remains to be seen. We choose to remain hopeful. What else can you do after a year like 2020?

For the purposes of this piece, a “Film of 2020” is a feature that had an Academy Award-qualifying theatrical opening, a local festival premiere, or an exclusive online premiere (virtual cinema, streaming, or VOD) between Jan. 1 and Dec. 31, 2020.

Cait Lore

20. The Vast of Night

19. Shirley

18. Markie in Milwaukee

17. The Painter and the Thief

16. Feels Good Man

15. Kajillionaire

14. Horse Girl

13. House of Hummingbird

12. The Assistant

11. First Cow

10. Collective

When a fire broke out at the Colectiv nightclub in 2015, 27 Romanians lost their lives, and another 180 were injured. The tragedy also incited political action. Scores of young people took to the streets, expressing outrage over Colectiv’s lack of fire exits and overall absence of accountability. Tensions heated even further as 37 more Colectiv fire victims died, this time over a series of months in their hospital beds, all of them suffering a shocking level of neglect while under the care of their doctors. It was during this period that director Alexander Nanau picks up his camera, following his instincts to a Romanian newspaper, the Gazeta Sporturilor, where the investigative journalists begin to uncover mass corruption throughout the Romanian healthcare industry. Collective, the observational documentary that rose out of Nanau’s footage, unfolds in real time, both in his film and the post-Covid world around us. Collective brings audiences close to the courageous individuals — both journalists and everyday people — fighting against corruption, tenacious even in the face of defeat.

9. System Crasher

Nora Fingscheidt’s explosively tender System Crasher tells the story of Benni, a 9-year-old girl whose antisocial behavior is so extreme, not even the German foster-care system knows how to support her. Fingscheidt first heard the term while shooting another project, a documentary feature about Germany’s women-only homeless shelters. When a child turns 14 and the system still doesn’t know what to do with them, they get left in these “dead-end” spaces, thrown into the adult world at a time when they can barely function as children. But why is the onus placed on the child? A term like “system crasher” seems to suggest an act of agency. Fingschedit’s wise new drama disagrees: It’s the system that’s broken, as social workers bump up against the system’s limitations. But Benni is an aggressive child capable of extreme physical violence. Audiences are asked to stare deeply into her pain, seeing the line between abuser and abused, which makes this one of the year’s most challenging features. A work of radical compassion, it also makes for the most convincing love story of 2020.

8. Nomadland

A lightness of touch and deep commitment to naturalism characterize Nomadland as an American road movie with the sensibilities of slow cinema’s greatest auteurs. A widowed wanderer, Frances McDormand’s Fern, hits the road in search of her own private landscape. The most action this “Western” sees is a plate shatter. It’s one of Fern’s most treasured objects — of which she has so little of — but in reality it belongs to McDormand’s real-life grandfather. The name Fern, too, comes from the actor: It’s what she plans to change her name to, after she’s finished with the movie business. Director Chloé Zhao, in collaboration with McDormand, translates the actor’s own personal history onto the film, weaving in and out of fact and fiction, invoking locations from the 2017 nonfiction novel, on which it is loosely based. The rest is a collaboration between Zhao, McDormand, and their largely nonprofessional cast. Spare but grand, Nomandland is a film of quiet strength and resounding beauty.

Carlo Mirabella-Davis’ directorial debut is an introspective and perversely funny investigation into gender, genre, and class. It also might be the first film to sit comfortably between The Shining and Now, Voyager. Haley Bennet plays Hunter, a former artist and newly pregnant housewife, who finds herself increasingly compelled to consume dangerous objects. Yes, Hunter’s decisions will absolutely make audiences cringe. But here’s the real kicker: Hunter’s (neurotic) compulsions actually make sense. And what a performance at the center! Watch for the quiet storms that pass through Hunter’s eyes as she smooths her blond bob, pulls at her dress, and smiles prettily for her husband. Bennet’s face, as it turns out, is a lesson in acting and Mirabella-Davis’ script more than keeps up with her.

6. Vitalina Varela

With Vitalina Varela, Pedro Costa has crafted his most technically astounding and perhaps deeply felt work. Near all of the shots are static sequences, carefully curated, where every beam of light is measured and accounted for. The resulting film is hypnotizing, almost surreal in its hyper-slow study of space, light, and shadow. At the center of the film is the titular Vitalina, who made her first appearance in Costa’s 2016 feature, Horse Money. The film is co-written by Varela, a nonprofessional performer, which allows it to function as a kind of poetic memoir to her dark night of the soul. Shot almost entirely at night, this mediation on memory features some of the most indelible images of Costa’s career. Nothing so minimal has ever felt this full, and no screen — however small — can deaden the power of these images.

5. Dick Johnson Is Dead

Docu-fantasy Dick Johnson Is Dead sees Kirsten Johnson and her titular father, Dick, prepare for the long goodbye. At 86 years old, Dick isn’t yet dead, but the immutable question of “when” draws near. Dick has been diagnosed with dementia, and although it is still early days, the two know what to expect: They lost Kirsten’s mother the same way some years prior. After 2016’s Cameraperson, Johnson’s Varda-esque approach to documentary had been established. Here she turns the lens further inward and onto her beloved dad. “Can I make a movie about you dying,” she asks. To which he agrees — anything to spend more time with his daughter. What he might not have realized is that she literally wants to film him dying. Over and over again. Still sprinkling in vérité scenes along the way, in which father and daughter speak candidly, the film breaks into an absurdist comedy. With inspiration from Looney Tunes, and the help of a stunt crew, Kirsten produces stunt after stunt for her father to execute. The first of which involves dropping an air conditioner on poor Dick’s head. In another, he tumbles down the steps. Off screen we hear Kirsten, shouting that his leg would look better from a different angle. As they laugh together, peeling back layers of artifice, they create a space to confront death, albeit from a safe distance. But time marches on. And as Dick grows more disoriented and forgetful, painful conversations emerge, presented in a vérité style. This all makes for an achingly beautiful film about life, death, and the power of cinema. Film your loved ones why you have them. Movies last longer than memories, after all.

Odes to heartbreak and longing, delicious and lonely, float above a reggae beat — that’s lovers rock. This era of Black British reggae scored many a Saturday night in ’70s and ’80s London. Lovers Rock depicts one of those nights, in almost real time, as young first- and second- generation West Indians gather at a West London home, dancing for hours, sharing in musical euphoria. A change in records shifts the mood. Janet Kay’s “Silly Games” overwhelms the dancefloor with a woozy elegance. Young women, looking glamorous and free, swirl around the space as director Steve McQueen’s immersive camerawork picks up the little details: soft glances, hands moving across fabrics, and sweet nothings whispered into ears. The crowd sings the song over and over, long after the track ends. Ten minutes into the scene and they’re still singing the chorus, long after the track has ended — it’s audacious, sure, but it’s also utterly transportive.

What if this painting could move? If the materials could speak? Can a film set be a workshop instead? This is the line of thinking that would bring David Lynch to make Eraserhead in 1977. But it’s somewhere between illusionist-director Georges Méliès and the “listening eye” of Walerian Borowcyzk that Cristobal León and Joaquín Cociña might locate their stop-motion debut. Presenting itself like a Latin American Brothers Grimm tale, The Wolf House presents the story of Maria, a young woman who escaped Paul Schäfer’s real-life Nazi cult in the south of Chile. But it may be best to think of The Wolf House as a performative documentary. Candles burn in real time as materials change and transform. Here the invisible hand of the puppet master provides raw, kinetic energy to every frame, often granting irreverent humor to the papier-mâché horror. A colossal feat of ingenuity, this nightmare-comedy of national trauma is one of the best stop-motion features in decades.

2. On-Gaku: Our Sound

Kenji, a high-school delinquent, did not steal his guitar. Not technically. It was handed to him. A man, chasing after a petty thief, put it there, in his hands, outside the corner store, a place where he can often be seen sitting or standing, staring into nothingness. That’s one thing Kenji understands: boredom. He is so bored, in fact, that his languor verges on something spiritual. But now his life is different. He has a guitar! He also has two friends, Ota and Asakura. Now, they are a band. No previous musical experience? Who cares! On-Gaku’s director doesn’t have any, either! Kenji Iwaisawa came to this project entirely on his own: no budget, no filmmaking experience — nothing. He spent seven-and-a-half years on this project, adapting Hiroyuki Ohashi’s own self-published manga, and 40,000 hand-drawn frames later, he had a movie. Closely involved in the production, Ohashi watched Iwaisawa develop his own idiosyncratic style, meeting the underground comic’s outsider aesthetic. On-Gaku is rotoscoped, with watercolor backgrounds, and occasionally breaks into more abstract representations to express the joyous celebration of music and the creative spirit. The results are explosive — frequently hilarious and full of heart. As modest as On-Gaku might seem, this is a pure work of art. And if that’s not enough for you, well, in the immortal words of Nitsun Abebe: this one’s more punk than a black-flag tattoo, folks.

1. I'm Thinking of Ending Things

Some 20 years ago, Charlie Kaufman's first major work, Being John Malkovich, was released into the world. Not long after, film academic B. Ruby Rich pissed off a generation of queer cinephiles when she declared Kaufman’s work as the logical culmination of New Queer Cinema. (Her term, by the way, coined 10 years prior.) It was a cheeky and original movie about gender confusion and identity destabilization, using celebrity worship as its vehicle. It also grants lesbians a happy ending, she quips. How many Hollywood films do that? Well, here’s an even bolder question for you: How many films feel so alive that they seem to be thinking for themselves? Without speaking on the plot — you likely already know it, anway — I’m Thinking of Ending Things queers our understanding of the film form by simulating the perpetual motion of thought. Over the course of a dinner scene, our protagonist’s parents go from young to old and back again. His new girlfriend — played by Jesse Buckley, utterly brilliant here — may be someone named Lucy. Or is it Yvonne? Is she an artist? No, she’s a poet. Wait, now she’s Pauline Kael! These on-screen representations of identity, in the most conventional sense, cannot stay fixed. And it shouldn’t: Who we are is an amorphous concept, as is the film. Even the objects of a childhood bedroom provide existential complications, bleeding into our understanding of whos and whats. It’s not all philosophy, however. This may be Kaufman’s most deeply intimate film to date. Surpassing even Synecdoche, New York in how close Kaufman brings us to his mindspace. If all great philosophy secretly doubles as memoir, can the opposite be true? This radical feature makes a compelling case for just that. Leave it to Kaufman to push film philosophy, yet again, into the future. All great philosophy doubles as memoir.

Kayla McCulloch

10. Natalie Wood: What Remains Behind

All one has to do is watch Rebel Without a Cause (1955), West Side Story (1961), or Splendor in the Grass (1961) to reaffirm just how great a talent Natalie Wood was. However, it’s not easy to ignore the actress’ tragic and mysterious death — a probable drowning at the age of 43 — that still looms over her legacy nearly 40 years later. Natalie Wood: What Remains Behind is less concerned with providing a general overview of her career and more interested in discussing the star’s private life, her family, and the questions surrounding her death from the perspective of her children and her partners — specifically the surviving Gregsons and Wagners. It’s gut-wrenching to see how her passing still has a hold on each of their lives, and it’s hard to imagine a better biography on the star thanks to the close collaboration of her blood relatives and family friends. This is ultimately why What Remains Behind stands out from the plethora of other by-the-numbers Hollywood docs.

9. I'm Your Woman

It turns out that Amazon and Rachel Brosnahan can deliver more than one notable period piece. Unlike their first production, Amy Sherman-Palladino’s The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel (2017- ), I’m Your Woman doesn’t have anything funny to say about the lonely life of a housewife: Director and co-writer Julia Hart’s argument is decidedly more tragic than comic. When husband Eddie (Bill Heck) brings home a baby one evening, Jean (Brosnahan) — who has long wanted a child but has just as long been denied one — doesn’t know what to think. This uncertainty grows even stronger after she’s whisked from her home in the middle of the night and told that her husband is missing and the mob is coming for her next. It’s a hero’s journey of a different sort, highlighting the strength and determination of a mother who loses everything and has nowhere to run as she evolves from nobody to somebody. Its pace is much slower than what people have come to expect from the crime-drama genre, but I’m Your Woman makes it feel like a necessary (and impactful) change.

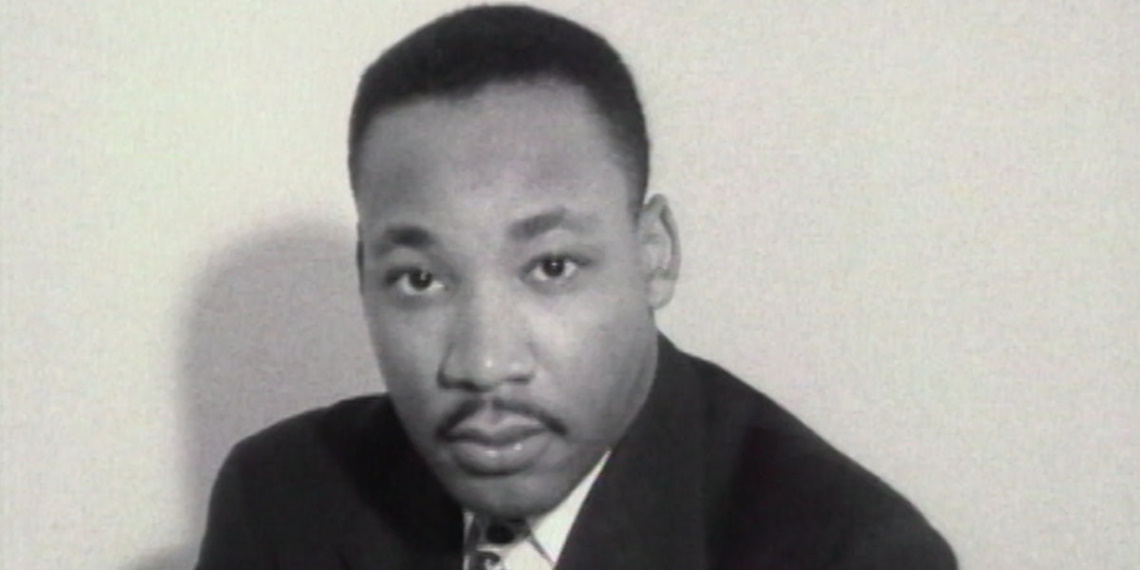

8. MLK/FBI

Longtime Spike Lee collaborator Sam Pollard’s latest documentary, MLK/FBI, wastes no time getting to the point: The United States government systematically spied on and harassed an American citizen until he was assassinated in cold blood. Despite being a devoted Baptist minister and a beloved civil-rights leader, Martin Luther King Jr. was viewed by some as a dangerous radical — especially in the eyes of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. This isn’t just a theory, either. Pollard combines newly declassified information with rare archival footage to craft a narrative more engrossing than any Hollywood biopic treatment could hope to be. Even if these revelations aren’t news to the viewer, Pollard’s skills as an editor make him an excellent director — MLK/FBI moves swiftly and doesn’t pull any punches as it educates and eviscerates.

7. Dick Johnson Is Dead

Director Kirsten Johnson’s family is the type to laugh at a funeral. That’s no joke. Dick Johnson Is Dead is a cathartic and darkly comedic look at what a father and a daughter go through when he’s approaching death’s doorstep and she’s filming it. By confronting their biggest anxieties about his impending doom, they’re able to overcome (or at least attempt to overcome) some of their fears and walk toward the end, hand in hand. Yeah, it’s sorta twisted, but it’s more heartfelt than anything. (And, for what it’s worth, Dick Johnson is easily one of the most lovable subjects to be put on screen in recent memory.)

Somewhat of a lesser-known title available to stream at last fall’s virtual St. Louis International Film Festival, L’autre (also known as The Other) is a profoundly original exploration of time and grief unlike anything else in years. Hailing from France and still without a U.S. distributor outside of the festival circuit as of this publication, L’autre is going to be a difficult find, but it’ll be more than worth the effort to track it down. Director Charlotte Dauphin blends dance and drama with an experimental structure to create a film that cuts deep and then keeps going. With a runtime of just more than 75 minutes in total, L’autre spends so much time in the mind of protagonist Marie (Astrid Bergès-Frisbey and Anouk Grinberg) that it leaves no room for contemporary genre tropes or trappings. It’s a knockout, to say the least.

5. City Hall

Last year marked the start of Frederick Wiseman’s seventh consecutive decade as a documentary filmmaker, and if City Hall is any indication, the nonagenarian is still doing work in the early ‘20s that’s just as vital as his output from the late ‘60s. Although some may be turned off by the run time, City Hall is four-and-a-half glorious hours of the day-to-day processes that keep the city of Boston running under the guidance of Mayor Marty Walsh. By exploring every imaginable angle at every level of the city, from weekly trash collection to annual city budget meetings, Wiseman paints a sprawling mural that only gets more intricate the longer attention is paid to it.

4. Borat Subsequent Moviefilm

Who would’ve guessed that a sequel to Borat (2006) released nearly 15 years after the original would not only be as sharp as the first but also just as funny? Borat Subsequent Moviefilm, which sees Sacha Baron Cohen reinhabiting the role of Borat Sagdiyev alongside Maria Bakalova as his teenage daughter, Tutar, flips the script on its predecessor by transforming the title character from a magnifying glass on society to a full-length mirror. Instead of using this caricature of a Kazakhstani journalist to expose America’s prejudiced underbelly, Cohen uses Borat as a way to show audiences all the ways the country is so proudly, openly beyond satire. Plus, though Cohen never misses a beat here, Bakalova is the one who elevates Borat Subsequent Moviefilm from a well-crafted lowbrow comedy to something with some real heft (and maybe even some real-world consequences) to it.

Given the many relevant conversations being had about a renewed sense of accountability and ethics in the workplace, it would be easy for a filmmaker to come along and make a movie that capitalizes on the zeitgeist. Imagine: a lowly office worker, fresh out of college, who has the gall to challenge the patriarchal power structure of the white-collar world and successfully topples an entire industry in the process. The Assistant is not that film, and it’s actually better for choosing not to succumb to this kind of well-meaning but ineffective fantasy. Instead, through the lens of one of those menial office workers, Jane (Julia Garner), director Kitty Green homes in on the mundanity of the microscopic actions that inevitably land higher-ups in hot water. It feels hopeless, and perhaps it’s because there truly is no hope things will get better until there’s some significant, ground-shaking change that takes place. It’s a heavy message, to be sure, but it needs to be said. The Assistant says it ambitiously.

Autumn de Wilde’s take on Jane Austen’s most famous comedy of manners, Emma, faced a seemingly impossible task almost as soon as the film was announced. With Amy Heckerling’s cult classic Clueless (1995) long considered the preeminent Emma adaptation and one of the finest Austen movies ever made, how could this new version even try to compare to its glory? As it turns out, de Wilde’s decision to simply stick to the text and amp up the style was the best possible move she could’ve made. It also helps to have Anya Taylor-Joy in the title role: Her full commitment to the part coupled with her impeccably dry comedic timing makes her spin on Emma a real contender for best performance of the year. Add in a batch of perfectly cast supporting roles — namely Bill Nighy’s Mr. Woodhouse, Mia Goth’s Harriet Smith, and Miranda Hart’s Miss Bates — and you’ve got a recipe for the sweetest, most decadent dessert of 2020.

The last thing we — as a collective audience — need is another hagiographic and vain puff piece about a wealthy celebrity. Why, then, is Miss Americana sitting here in the top spot? For starters, it’s neither hagiographic nor vain: Taylor Swift, the focus of Lana Wilson’s up-close-and-personal documentary that tracks the aftermath of the singer-songwriter’s 2017 album reputation, shies away from the vapid, the flattering, and the surface level to reveal something much more complex than the typical behind-the-scenes music doc. From her mother’s battle with cancer to her own struggles with her body image over the years to her fight to break her political silence against the best wishes of her team, Miss Americana is endearing instead of enraging, humanizing instead of humiliating, and emotional instead of egotistical

Joshua Ray

Another 20: Alone; Another Round; David Byrne’s American Utopia; Earth; Fire Will Come; The Forty-Year Old Version; His House; José; MLK/FBI; Never Rarely Sometimes Always; On the Rocks; Red, White and Blue; Sound of Metal; Sunless Shadows; Sylvie’s Love; Tenet; Tommaso; The Vast of Night; Welcome to Chechnya; Zombi Child.

20. Malni - Towards the Ocean, Towards the Shore

Sky Hopinka, who is emerging as an important experimental filmmaker, presents personal and poetic esoterica about Indigenous tradition in a world that marginalizes its people.

19. Feels Good Man

Pepe the Frog’s trip down a radical rabbit hole from stoner to fascist is the most fun and frightening semiotics lesson that there’s ever been.

18. Mangrove

The five “episodes” of Steve McQueen’s Small Axe are better together, but each stands confidently on its own, with Mangrove’s quality thoroughly embarrassing that other riot-incitement trial film from 2020, Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7.

17. Midnight in Paris

Defiantly not a certain overrated film with which it shares a title, Midnight in Paris is a joyous document of a predominantly Black high school in Flint, Mich., preparing for its proverbial Big Night: prom.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa meets Kiarostami halfway in an occasionally jejune yet incisive tale of internal and external dislocation.

15. Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets

“It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine)”

14. Minari

The American dream is often a nightmare, and for the Korean immigrant family in the exquisite Minari, it tests their resiliency to its breaking point.

This ostensible “Dark Universe” riff on The Invisible Man (1933) turned out to be a retooled Gaslight (1944) and a cinematic funhouse ride whose shocks were in service of eliciting great empathy.

Depicting a revolting revolt of sadistic masochists and masochistic sadists, Liberté is the most gorgeous film of 2020 that’s impossible (not) to look at

9. (tie) I'm Your Woman; The Whistlers; The Wild Goose Lake

“What does the audience want from a film? A girl and a gun.” The quote and its variations – often attributed to Godard but actually from Griffith – has been taken by some as cheeky, pithy film theory. It’s also kind of facetious bullshit that nevertheless manages to get close to pinpointing the titillation cinema is capable of providing. Nowhere are these stand-ins for sex and violence more comfortable bedfellows than within the film noir. The genre (or style, if anyone’s still asking Paul Schrader for answers) was born out of cultural neuroses, and its best progeny are no different. Julia Hart’s New Hollywood noir, I’m Your Woman, is the spark between the flints of an admittedly binary battle of genders. With his neon neo-noir The Wild Goose Lake, Yi'nan Diao writes a bloody missive to the abuses of his Chinese government. The Whistlers finds Corneliu Porumboiu puzzling over fractured signs and symbols within a mire of double- and triple-crossing criminals. Stories of what people will do when pushed beyond their limits have proliferated in real life, but with generic metaphors in tow, this trio found similar truths with cinematic pleasure.

7 (tie). Collective; Dick Johnson Is Dead

Death colors nearly all memories of 2020. For a year packed with superlative nonfiction filmmaking, things were no different: a pair of the very best also happened to be preoccupied with mortality. Although Alexander Nanau’s searing, stomach-churning, and ultimately triumphant Collective made an indelible mark at pre-Covid film fests earlier in the year, its truths about Romanian government corruption during a health crisis were multiplied and made identifiable on a global scale while a pandemic ravaged – and continues to ravage – the world. As witnessed on those same festival screens, with Dick Johnson is Dead, Kirsten Johnson documented her dementia-stricken father’s life by imagining his death with comic morbidness and freewheeling cinematic inventiveness. She was able to achieve what millions dealing with sudden mourning this year could not: meditating over the loss of a loved one on their terms. If an absence of empathy within certain populations has become more apparent as time marches on, Nanau and Johnson’s films about the preciousness of human life are proof of its existence elsewhere.

4 (tie). Bacurau; Ghost Tropic; Vitalina Varela

A trio of nightmares of colonialism, Juliano Dornelles and Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Bacurau, Bav Devos’ Ghost Tropic, and Pedro Costa’s Vitalina Varela are proof that the seventh art is the only one capable of replicating dreams. Made oneiric by methods as varied as their respective collision of disparate genres, striking Antonionian architectural tableaus, and digital filmmaking-as-painting, these death-haunted odysseys of alienation are connected to the subconscious’ source of human experience. They’re filmmaking as psychoanalysis, exposing humankind’s innate desires for self-actualization and connection to community and land through distinctive logic and mesmeric imagery.

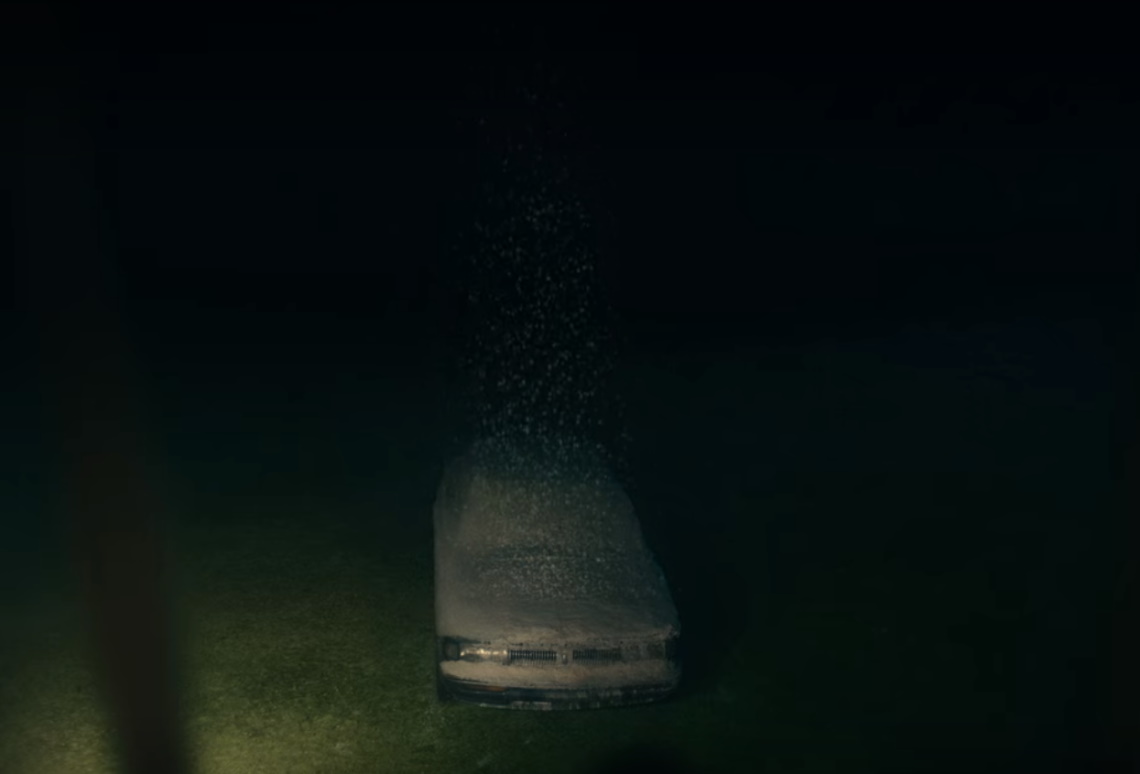

A single drop of sweat rolls down from the ceiling along some worn wallpaper. It’s the collective product of the partygoers at the heart of Lovers Rock, the crown jewel of Steve McQueen’s superb Small Axe anthology. The close-up cutaway to the group perspiration – a brief bolt of lightning among similarly electric moments present throughout the film – is a literal sign of just how hard the dancehall-DJed gathering goes. With a palpable ache for physical connection, Black bodies endlessly bump and grind in a space that is graciously exclusively theirs. The ad hoc dance club is a respite from the violently racist ’70s London in which the Caribbean immigrants reside, a reality that exists in the margins of Lovers Rock and at the center of Alex Wheatle; Red, White and Blue; Education; and Mangrove. The bodily result from this joyous celebration of cultural identity also works as a metaphor for community, and the shot gestures to the power of a galvanized group of individuals. Likewise, while Lovers Rock finds McQueen with a newfound intuitiveness, when collected together, his Small Axe films represent the director’s most lucid work yet.

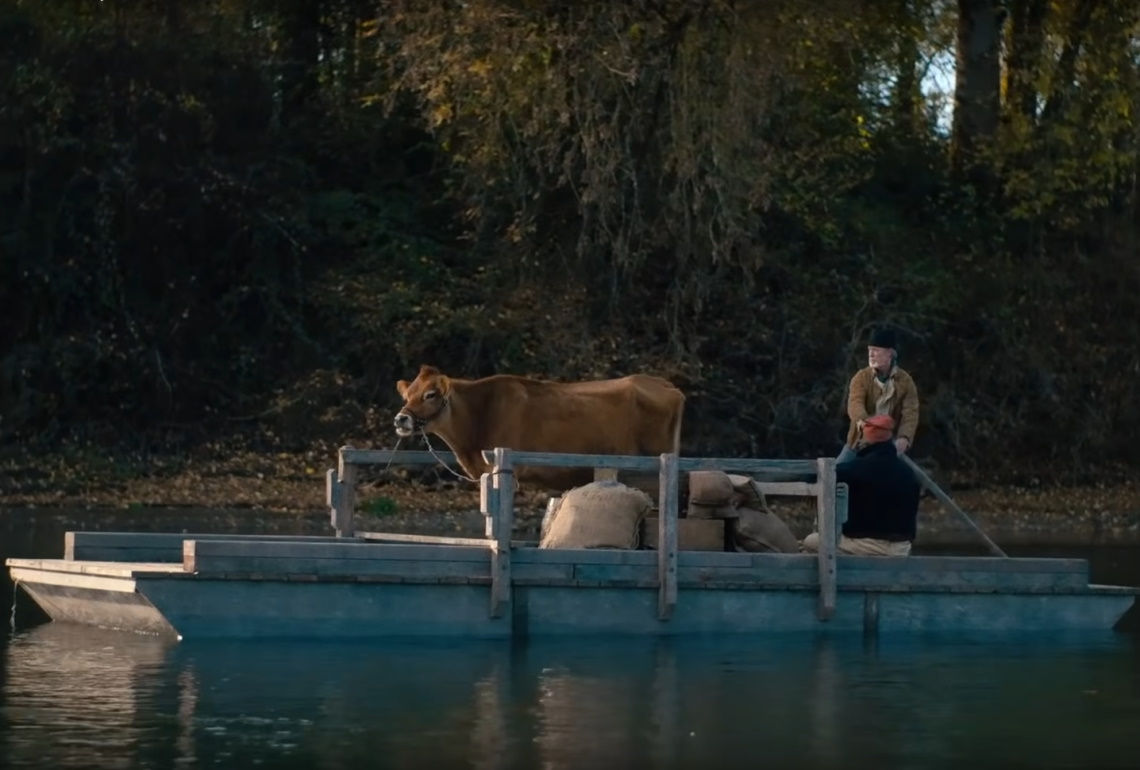

1 (tie). City Hall; First Cow

Kelly Reichardt’s end of the beginning and Frederick Wiseman’s beginning of the end (at least for the cynics): First Cow and City Hall are aesthetic opposites presenting different end points in the story of the United States. The neorealist legend-in-the-making and the 90-year-old documentary legend find one point of intersection by suspending their viewers in a liminal space without awareness of passing time – the fire of their awe stoked by the most sublime and subtle movements. In her 19th-century-set buddy movie about a dangerous yet delicious capitalist venture, Reichardt employs a dreamy stillness made rich by grainy Super 16 mm filmstock in the square-ish Academy ratio. Wiseman’s 4.5-hour compilation of the gears of the well-oiled machine that is the Boston, Mass., city government fills the screen with the director’s fly-on-the-wall vision of reality, keeping digital eyes on the “action” of work with an indelible clarity.

For all their differences, the films’ ends are remarkably twinned. Within each are portraits framed by notions of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, but the emphatic passions present are tempered by systemic obstacles in place. Of her magical-realist-leaning fable, Armond White said, “Kelly Reichardt condemns American capitalism as racist and homophobic.” No shit. Although White means that as a negative, he and Reichardt are both correct, while Wiseman’s document doesn’t seem to disagree. However, by mounting products of such artistic ingenuity, the directors’ unintentional double feature suggests – in the values of each and within their texts – that collectivism is far more powerful than individualism; it provides glimmers of hope for the American experiment.

Andrew Wyatt

Best Documentary Feature Nobody Is Talking About: Coup 53

Best Narrative Feature Nobody Is Talking About: True History of the Kelly Gang

Best Animated Feature Nobody Is Talking About: A Shaun the Sheep Movie: Farmageddon

Best Performances Nobody Is Talking About: Shaun Parkes in Mangrove and John Boyega in Red, White and Blue

Best Documentary Mini-Series: I’ll Be Gone in the Dark

Best Narrative Mini-Series: Devs

Best Antagonist: Terry (Rachel House), Soul

Best Bad Off-Broadway Play-Within-a-Film: The Forty-Year-Old Version

Best Grandma: Lucky Grandma

Best Reason Not to Give Up on Superhero Movies: Birds of Prey

Best Weird Sexual Tension: The Painter and the Thief

Best Windows: Swallow

Nastiest Production Design: The Platform

Weirdest Directorial Debut: Romola Garai, Amulet

Best Cinematic Embodiment of 2020: She Dies Tomorrow

Honorable Mentions: Another Round, Coup 53, Emma., Ghost Tropic, The Invisible Man, Mangrove, Minari, The Nest, Palm Springs, Possessor, Sorry We Missed You, To the Ends of the Earth, True History of the Kelly Gang, The Vast of Night, Welcome to Chechnya.

25. The Twentieth Century

24. Vitalina Varela

23. Red, White and Blue

22. Night of the Kings

21. Zappa

20. Promising Young Woman

19. House of Hummingbird

18. Bacurau

17. La Llorona

16. Rewind

15. The Wolf House

14. Sound of Metal

13. Relic

12. Wolfwalkers

11. Nomadland

10. Gunda

Gunda the sow stirs and rises to greet a world that is cruel but not sunless. Piglets squeal and scrabble for a teat, seeking their mother’s warmth. Chickens creep (and hop) through the buzzing, snapping underbrush, every scaly step placed slowly and deliberately. Cattle chew and stare and fidget like wary sentries, standing nose to tail amid the circling flies. The piglets grow plump and strong, Gunda snuffling after them with a mother’s exhausted devotion. And then – her farrow is gone, snatched away by Man for reasons she cannot fathom. She only knows that her piglets were here, and now they are not, and there is no solace to be found in the hay and the dust.

Fox Rich and her family are waiting. They’re fighting, too, of course – fighting tirelessly for the release of husband and father Robert from the Louisiana prison where he has been condemned to spend six decades. Mostly, however, Fox is waiting. Waiting for justice to roll down like water, waiting for the iron talons of a racist, carceral state to hear her pleas. Her life goes on, but her reality never changes. She matures and thrives, and yet she is also frozen in amber, forever the partner of a man who is absent – a dotted outline where a husband should be. Her bright, apologetic tone with the court clerk never wavers, but she is growing tired and angry. Still, she waits, cradling the flame of hope and bottling her tears for her beloved’s return.

There’s no time for silly games, but we play them anyway. And why not? This is London in the very early ’80s, the Red Stripe is cold, and the dance floor is hot. Dennis Brown and Bob Marley are here, along with Junior English, Carl Douglas, the Delfonics, the Revolutionaries, and more. Men prowl and women spurn, but everyone pairs up eventually, even if it’s only for one song. The air is thick with allspice and weed and cheap cologne. Sweat trickles and bodies grind. Strong hands squeeze a sequined ass. A shard of glass slices the night air. Eat, drink, and be merry. Tomorrow we return to the White world, but tonight is for Black love.

7. Never Rarely Sometimes Always

Autumn’s eye shadow sparkles and her pink jacket shimmers, but the words she sings betray her anguish. She’s not alone, however: Skylar is there. Together they endure the daily indignities – the fondling hand – and together they will find a way. Together they will pocket the cash, together they will pack a suitcase, together they will go to New York City. They will take care of it. They will navigate the roaring subway, the unfamiliar streets, and the wolves in their path. They will bicker and wound each other, but in the end, Skylar will stay, the girls bound by hooked pinky fingers. Autumn will answer the questions, face her fears, and take control. Her name is Autumn Callahan. She was born Aug. 19, 2002. She is having an abortion.

6. Dick Johnson Is Dead

The cameraperson turns her lens on her dear, not-so-departed father. She recalls how he was, savors how he is, and imagines how he might make his final exit. Crumpled at the bottom of a staircase? Exsanguinated by an errant nail? Brained by a falling air-conditioning unit? She envisions a thousand ghastly deaths but also a gleaming final reward, watching in jubilation as Dad spins Mom on a dance-floor cloud, showered with confetti and the hosannahs of haloed backup dancers. Fantasies that are grim, comic, and exultant rub shoulders with the stony reality that we are all shuffling toward: the diminishment and departure of those we hold dear, the ones who made us who we are. Kirsten Johnson is preparing for the grief, but in the meantime, she is filming, bestowing immortality on her father as only a filmmaker can.

5. Beanpole

In the USSR of 1945, the siege has been broken and the treaties have been signed, but the war rages on. Casualties are still being tallied, among them a fragile life that expires underneath the frozen weight of poor, shivering Iya. This loss frays her bond with her former comrade-in-arms Masha – a connection that is powerful, nourishing, and potentially poisonous. The postwar rubble is ensconced in a twilight where maimed soldiers beg for death, but flickers of malachite green pierce through the gloom: a scarf, a lamp, a wall of peeling paper, a dress on a woman twirling in agony and abandon. Is it the warning hue of a venomous creature? Or is it a fleeting glimpse of a different world? A world where we can love, heal, and dare to think about the future?

Wake up. Go into the city. Turn on the lights. Make the coffee. Respond to the emails. Set out the refreshments. Organize his schedule. File the paperwork. Wash the dishes. Blend his smoothie. Make his reservations. Answer his calls. Apologize. Pick up lunch. Clean up the stain. Sign the checks. Apologize again. Send the car for the girl. Keep your head down. Do your job. Be smart. Don’t make waves. Don’t worry. You’re not his type.

3. I’m Thinking of Ending Things

Lucy (Or is it Louisa? Or Yvonne?) is thinking of ending things. Her boyfriend, Jake, is nice, but still. There’s no future there. What begins as an interminable road trip and awkward meet-the-parents soon dissolves into a blizzard-lashed underworld molded from the past, present, and never-was. Something is profoundly wrong, but she can’t place what – she can only run her fingers over the old VHS covers and book spines in a futile search for answers. Except there are no answers here, because there’s nothing here but self-absorbed affectation: mere phantoms constructed of regrets, obsessions, and the great works of American musical theater. She contains multitudes, and yet she is less than whole, a void filled with useless trivia and withered dreams. But if this is a dream, who is the dreamer? You don’t have to go forward. Just don’t go into the basement.

A proto-Nick and Honey blunder into a spider’s den of misery, manipulation, and white-hot creative genius. Yet Ms. Jackson’s flame is guttering of late, suffocating on lassitude and bilious contempt. The Rose that has entered her parlor provides a rejuvenating spark, whispering a fiction in Shirley’s ear that reverberates with true-crime fact and scandalous fantasy. To birth it will require suffering, but suffering is something that Shirley knows. The story peers at her from the trees and kisses her on the neck, always fluttering just out of reach. Rose is part of the story, but it doesn’t belong to her. Shirley is the one who claws the words from her soul, scrapes their residue from the hollow of her skull. She’s the one who accepts the hurt. Stanley will love the book, of course. He will have some notes, of course.

The leading edge of the American Dream advances through the green wilds of Oregon, long before statehood had been inked and the custard of colonial civilization had completely set. An unlikely friendship is forged through mercy and gratitude, and from that friendship springs serene contentment – for a time, until the itch for Something More manifests. Even humble dreams require capital, so a dairy-centric heist is planned. Dough is fried, honey is drizzled, cinnamon is shaved, and the future seems bright. This is Kelly Reichardt’s America, however, where the Have-Nots rarely win, and the Haves never lose. The end has already been written, and the bones are already moldering in the earth. The best that a man can hope for is a promise from a true friend: Come what may, I will not leave your side.